Hi everyone! This is the first article in what will be a series delving into the fundamental mathematics that underlie the My Little Pony card game. Much of this may be intuitively understood after a few plays, but it's worthwhile to spell it out in detail.

This site and article are intended for experienced players, familiar with the cards and rules and turn sequence. For beginner material, you might try Krysto's Corner on tumblr, starting from this post.

Effective gameplay in the MLP CCG fundamentally revolves around one concept: deploying power as efficiently as possible per action invested. Here's the golden rule of building decks and gameplay tactics: Every action you spend must generate at least that much power at a problem.

If a card doesn't do that, it needs an extremely compelling reason why, or it doesn't belong in your deck. The gold standard for playability is one action to one power. Such cards exist in plentiful supply, with many in each color. Moving any 2-power friend from home also accomplishes this. As a convenient shorthand for that standard of converting each action into one deployed power, let's name it as the concept of par.

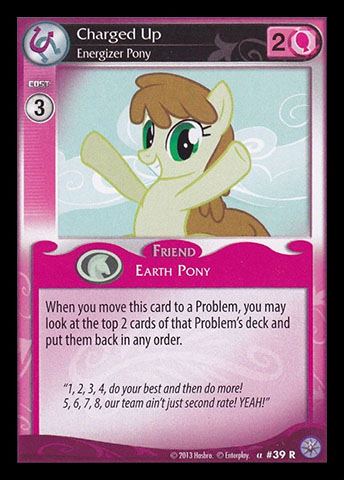

Why does this matter? Because your opponent is competing and racing for the same problems and points as you, with the same amount of action resources. If you play a subpar card such as Charged Up at 3:2 cost:power, your opponent can get better power for the same cost with a 3:3 such as Apple Brown Betty, or match your power for less cost with any 2:2 friend. They either gain an advantage on the ensuing faceoff or keep a surplus action to apply to the next problem. Winning games in MLP consists of developing an engine to break par as much as possible, getting more than one power per action spent, so you can confront problems and score points faster and more efficiently than your opponent.

The most readily available way to break par is to flip your mane character. If you can move her and meet the flip requirement, you have deployed 3 power for only 2 actions spent. If your opponent wants to win a faceoff at this problem, now they have to find a way to do the same thing. If they can't, then either you're ahead on the faceoff, or ahead in actions because they spent more to match your deployed power. And not only have you broken par here, you've created an engine that allows you to repeatedly break par throughout this game, by spending two actions again to move your three-power mane character each time she finds herself at home.

And like the mane character, any friend of 3+ power also represents an easy way to break par. They typically won't do so when initially played, but from home after facing off, you've got another chance to attack a problem with three power for just those two actions of movement cost. Conversely, moving any 1-power friend from home represents a poor play that will leave you behind an opponent who gets 2 power out of that same 2 cost by moving a bigger friend or playing one from hand.

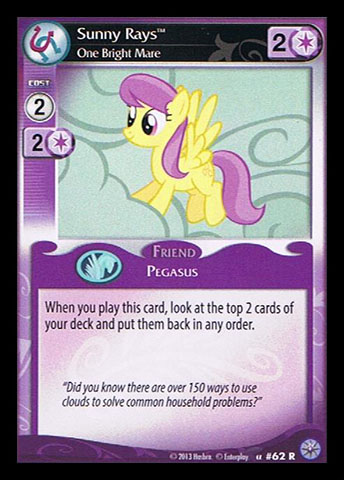

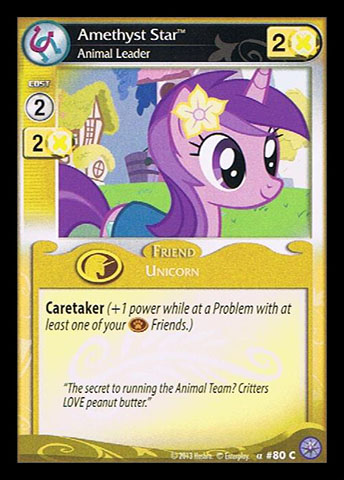

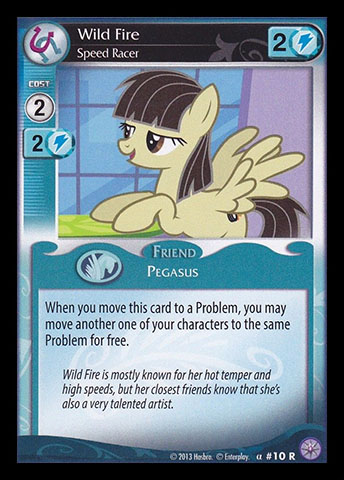

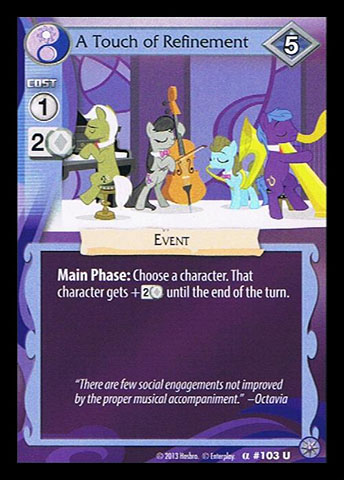

These cards each offer an easy way to beat par.

Now, par is not exciting alone. It's merely the minimum standard for playability. Most of the time you don't really want to play ordinary cards at par, just when it's a necessity of developing a color or flipping your mane. The best cards are those that break par quickly and with minimal dependencies, like how Amethyst Star does immediately with any critter or Wild Fire does as soon as she's moved. Most colors have sufficient supply of such cards that you should need to play fairly few at merely par, ideally none beyond those needed to enter your secondary color. (Pink is the exception, and performs rather weakly with hardly anything that breaks par, but that's another article.)

So now we see why blue decks can be so dominant. Rainbow Dash or Holly Dash with their "ride-along" abilities each typically deploy 5 or 6 power for a mere two actions, often able to confront a fresh problem immediately. An opponent not playing blue will have to spend several more actions to confront that same problem, while the blue deck saved its surplus actions for the next turn and next problem. Eventually the blue deck will find itself able to sweep multiple problems on a single turn, creating a highly advantageous double faceoff for a game-winning swing of points.

Even cards that generate more actions are really about beating par. Consider Twilight Sparkle, All-Team Organizer, who indirectly creates another way to break par. You might later play a friend such as Full Steam with four turns worth of Organizer's production, getting Steam's four power for an original investment of just Organizer's three cost. (You can't directly save up Organizer's actions, but as long as you spend hers on something else each turn, you can save one of your natural actions in its stead.)

The Danger Of Cool Things

"These cards do such neat stuff. Why am I not winning games?"

Welcome to the danger of cool things. The effects look like all sorts of spiffy, but consider the costs and you'll see the price of the party.

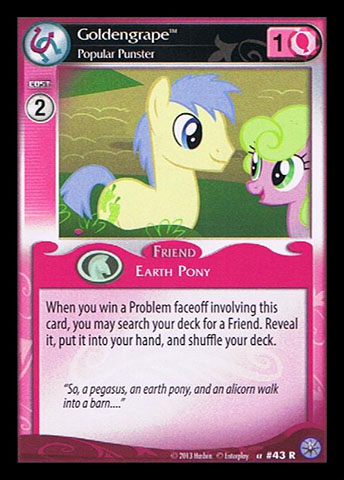

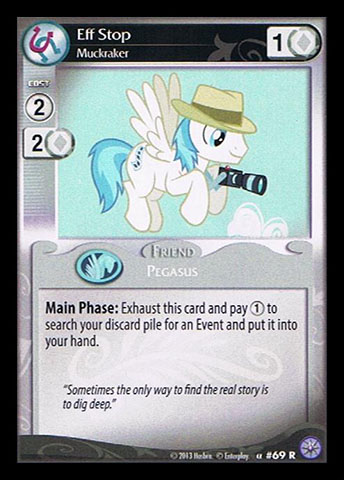

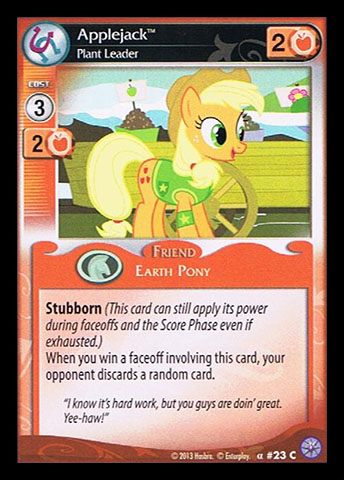

These cards are bogeys. Worse than par right out of the box. Any such card needs to do a lot of work to overcome that and break par. Most can't.

Goldengrape can get anything you want out of your deck, with the small condition of winning a faceoff. That's not so hard, so Goldengrape looks awesome, right? No. That cost of 2 for just 1 power means that either you went into the faceoff at a power deficit or spent more somewhere else to compensate. Goldengrape's inefficiency essentially means you were paying 1 extra for the right to tutor up that friend. How many friends can still break par at one over their face value cost? None directly, even Twilight Sparkle, Ursa Vanquisher plays for merely par, and only a few by indirect means like Forest Owl or Spring Forward or Rainbow Dash, Winged Wonder. Goldengrape needs everything to go perfectly to be worthwhile, and that's before considering the possibility that the faceoff swings against you and leaves Goldengrape a completely wasted investment.

Eff Stop works similarly, letting you pay one extra to retrieve a discarded event. Not many events are still worthwhile at one more than their face value. For example, Back Where You Began turns into a null operation at paying 2 to undo 2 actions worth of movement. Here's Your Invitation or Downright Dangerous mean you've paid 2 or 3 to remove a friend that cost only 1 or 2. Stand Still remains efficient at 1:2 action advantage, but it's the only such target. And even recycling Stand Still takes a lot longer than you think to pay off. Eff Stop costs two to play, so recycling Stand Still twice merely returns to par and you need three uses to get ahead. By that time the game will already be over. On top of that, there are more ways for Eff Stop to fizzle, maybe you don't draw a Stand Still, or the opponent is playing blue Swift friends that move again for only one action.

And Applejack, Plant Leader begins worse than par with an enormously long journey to recover. Even if you pull off winning a faceoff with her, you've paid one extra to force one discard, which is merely par in light of the pay-to-draw rule. Plant Leader only breaks par after two faceoff wins, an eternity of time in this game. (And even then the par break is only in the form of a forced discard, not in power or actions.)

None of these cards are unplayable. But they need some specific contingencies to go right to perform better than par, or else they represent a waste of an overcosted investment. Think long and hard about the cumbersome requirements for these sorts of cards before playing them over cards and colors that simply meet or break par on their own. You can play Eff Stop with a long and fragile and complicated route to action advantage via Stand Still, or you could play a simple card like Two Bits or Wild Fire that easily breaks par with minimal dependencies.

There also exist even worse cards, bogeys whose maximum payoff merely comes back to par and no better. Auntie Applesauce, Berry Dreams, Mint Jewelup, Ol' Salt. If you've followed this far, understanding the badness of these cards should come naturally.

"It's only one action extra, how bad could it be?" Plenty bad. That one action could be two power with anything like Watch In Awe, and eventually become a game-swinging difference on whether or not you can reach a critical double faceoff before your opponent wins instead.

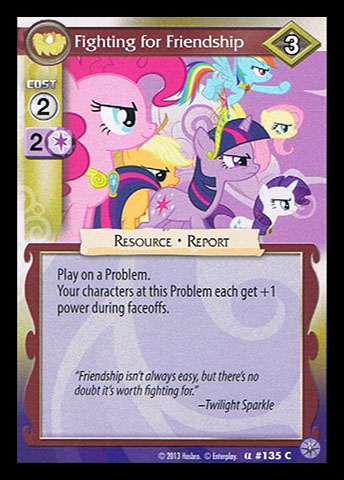

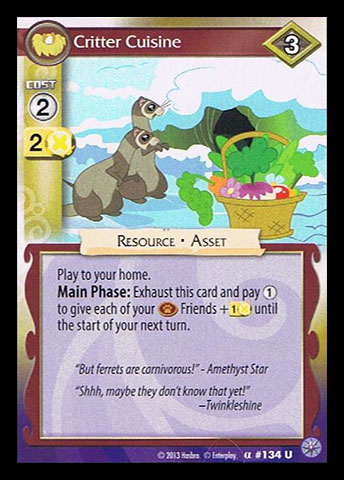

Resources can also be considered in light of the par principle. To use cards like Fighting For Friendship and Critter Cuisine efficiently, you must set up situations where they will provide more power than their own costs. More detail on this topic another time.

Obviously there do exist other factors guiding your gameplay besides action:power ratios. You're quite happy to pay extra for Rarity, Truly Outrageous when she's going to instantly win the game. But by and large, the principle of maximizing power for actions is the bedrock of how the My Little Pony CCG functions. Cards and decks that consistently break par by delivering more power than actions spent are those that consistently win games.

"The Danger of Cool Things" is the title of a seminal article on Magic: the Gathering. I stand on the shoulders of its giant in applying the very same point to MLP, to be cautious about doing things that look cool at the expense of correct efficient plays that win games.